Organoid research key to exploring relationship between Crohn’s and mental health

The answers to a crucial connection between the gut and the brain of individuals dealing with Crohn’s disease might lie in tiny, lab-grown brain and intestine organoids at the University of Saskatchewan (USask).

By Matt Olson, Research Profile and ImpactA multidisciplinary team of USask researchers is using innovative organoid models to explore connections between Crohn’s disease and mental health disorders.

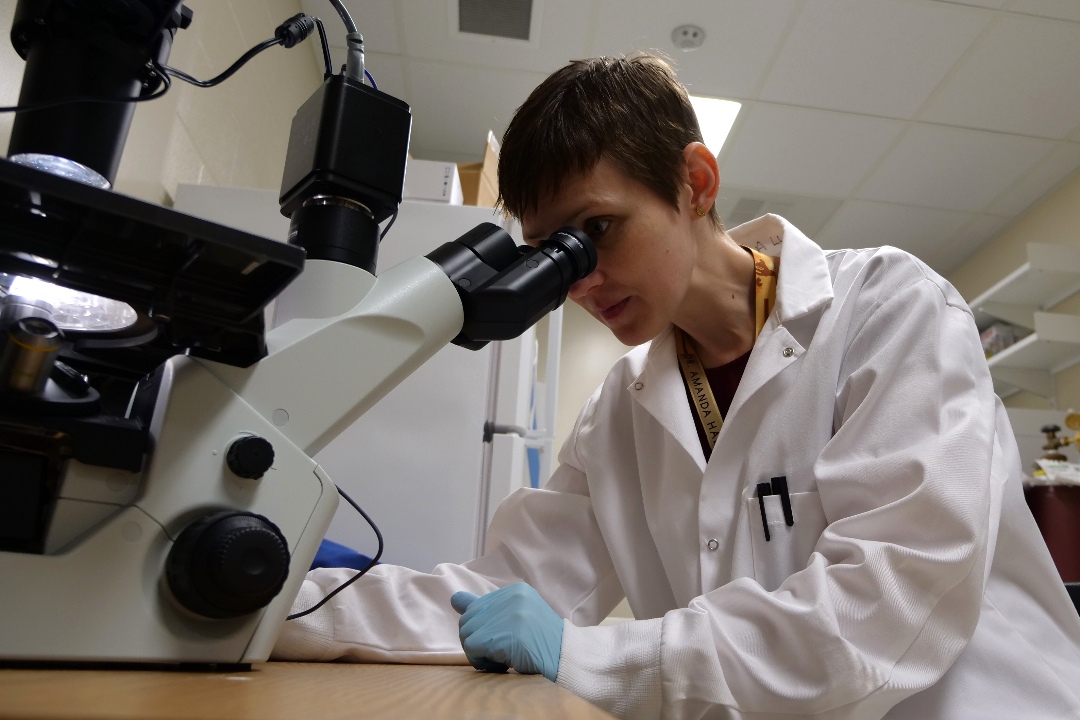

“We'll be basically building a miniaturized model of a Crohn’s patient to look at how the brain organoid interacts with the intestinal organoids to hopefully support the theory that this is one disease affecting the whole body,” said Dr. Amanda Hall (MD), assistant professor of surgery in USask’s College of Medicine and a pediatric surgeon with the Saskatchewan Health Authority (SHA).

The USask team received $150,000 over three years from the Saskatchewan Health Research Foundation (SHRF) Establishment Grant program to build out this research program.

The chemical and microbacterial connection between the brain and organs like the intestines – referred to as the “gut-brain axis” – is a well-documented phenomenon. A two-way communication system, the gut-brain axis is a connection between physical and emotional body responses.

While most work in this area so far has been conducted with animal models, Hall and her team hope to develop tiny intestinal organoids – cell clusters made from human stem cells and grown into intestinal cells – so they can test on a more human model.

Hall is working with Dr. Tyler Wenzel (PhD) in the Mousseau Lab in USask’s College of Medicine to develop the human organoid model. Wenzel’s lab has previously developed “mini-brain” models from stem cells, and the research team will aim to create an organoid model that replicates the gut-brain axis between intestinal and brain organoids.

By using the stem cells of individuals both with and without Crohn’s, Hall will detect if the inflammatory markers of Crohn’s disease can travel and affect brain cells.

“The brain is not just locked in by itself with no communication to the outside world. There’s actually quite a bit of crosstalk between the brain and the gut,” she said.

Hall and her team believe that the hormones and chemicals that cause bowel inflammation with Crohn’s could be travelling along the gut-brain axis and having a direct impact on the brain – and possibly causing depression, anxiety or a myriad of other mental health disorders.

“We've known for a long time that people who have Crohn’s disease have a two to three times greater risk of having a mental health disorder like anxiety or depression, and previously it was assumed you would develop a mental health disorder trying to cope with Crohn’s,” said Hall.

“Recent studies have suggested it’s a link in the inflammatory mechanism, and it’s one inflammatory disease affecting the whole body and affecting neurophysiology.”

If the physiological link between Crohn’s and mental health disorders can be established, Hall said it would have major implications for prescribing treatments for both conditions in patients.

“This has the potential to impact a large population of people who are suffering from a very complex disorder,” she said.

Other members of this research team include Dr. Sharyle Fowler (MD) and Dr. Tyler Wenzel (PhD) in the College of Medicine and Farinaz Ketabat, a PhD student in Biomedical Engineering.

Together, we will undertake the research the world needs. We invite you to join by supporting critical research at USask.