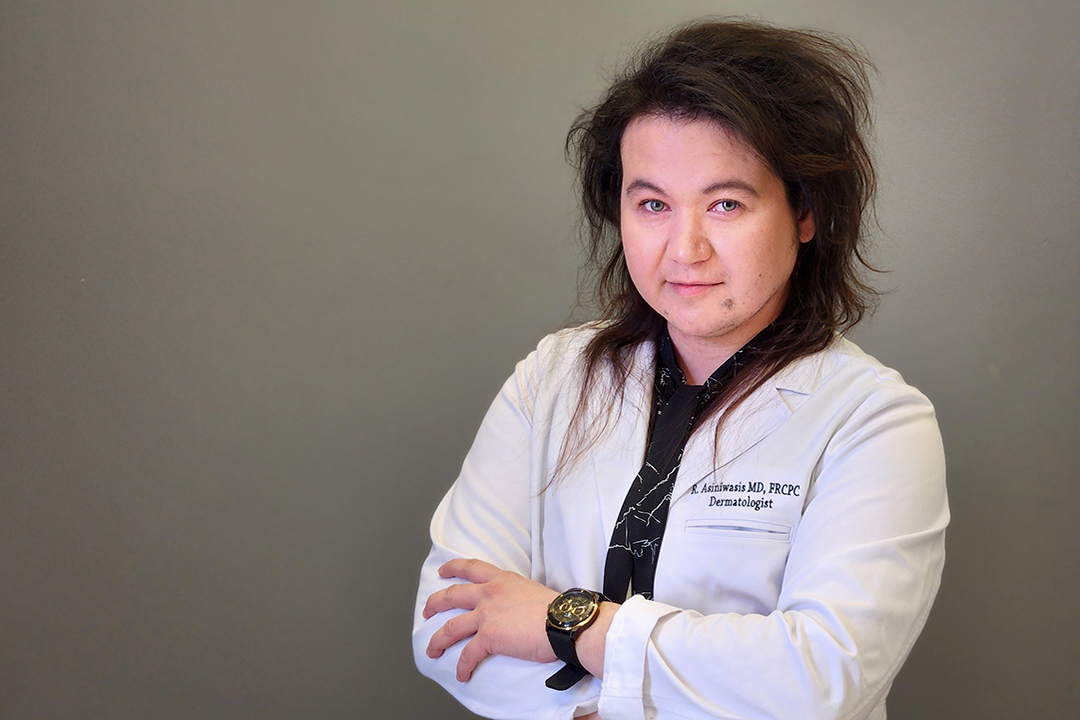

Scratching That Itch: Dr. Rachel Asiniwasis Targets Atopic Dermatitis

When Dr. Rachel Asiniwasis (MD) returned to the prairies after her dermatology residency in Toronto, she noticed a pattern among many of her pediatric patients. Hundreds of them were coming to her with itchy, raw patches of skin, the result of atopic dermatitis — eczema.

By Researchers under the scope, Office of the Vice-Dean ResearchListen to all episodes of the Researchers Under the Scope podcast.

Researchers Under the Scope is produced by the Office of the Vice-Dean Research in the College of Medicine.

“One of the biggest frustrations for me is when people say ‘oh, it’s just a skin problem’,” said Asiniwasis. “Itching in many ways is just as impactful as chronic pain,”

Atopic dermatitis is the most common chronic skin inflammatory disease. The vast majority of cases start in children under the age of five. At least one in every ten Indigenous children in Canada has some form of eczema. That figure rises to one in every four children in some Arctic communities.

"It is very, very impactful on multiple holistic levels,” said Asiniwasis, who said the itch and pain -- amongst other signs and symptoms in moderate to severe cases -- can lead to depression, ADHD, anxiety, and an increased risk of suicide.

“A lot of people learn to just live with this condition. If it's not optimally treated, you might see them have hospital visit for flares or secondary infection. And if, for example, if a child has severe disease and it's not controlled and they're not sleeping, that can affect their academic performance. So with eczema, it can get so bad that you can't sleep.”

In this episode, Asiniwasis admits she was late in choosing her specialty, only moving toward dermatology during her second year of medical school, after she met Dr. Peter Hull.

“I had a misconception that (dermatology) is a scientist that just made things like sunscreens in a lab,” she said. “He was the one who first exposed me to dermatology as being a manifestation of internal and external health.”

The prevalence of atopic dermatitis in her young Indigenous patients soon left her with more questions than answers. Shortly after the Covid-19 pandemic began, she enrolled at The George Washington University in Washington, D.C. to earn her master’s degree in clinical and translational research.

Two years ago, she conducted a survey of 50 dermatologists, nurses and family physicians who work in Indigenous communities across Canada. Atopic dermatitis was the most common skin disease reported by their patients, followed by bacterial infections. Other areas of interest observed by participants included acne/rosacea, scabies, and Hidradenitis suppurativa. Asiniwasis presented her initial findings at the Saskatchewan Health Research showcase.

Working with medical leaders in five southern Saskatchewan Indigenous communities, Asiniwasis was also granted permission and ethics board approval to perform a confidential chart review for hundreds of pediatric patients with atopic dermatitis. A number of those patients saw their uncontrolled atopic dermatitis devolve into secondary infections, often leading to hospital visits and multiple courses of antibiotics.

Asiniwasis hopes to publish her systematic scoping review of North American Indigenous Skin Disease by the end of this year.

"The literature's also showing high rates of bacterial skin infections, which is another part of the scoping review,” she said. “We're also seeing problems with chronic impetigo, boils, MRSA, all of these types of bacterial skin infections in those with uncontrolled eczema in rural and Indigenous children, across all fronts.”

She’s seen a number of patients with skin lichenification: something she refers to as ‘elephant skin’.

“It comes to a point where often our first line topical therapies don't penetrate and treat it, or it can take months,” she said. “We have to escalate therapy in these patients, so that can put them at risk for other side effects. We need to prescribe things like immunosuppressants, like methotrexate, or biologic targeted therapy if it's all over the skin. They can't be put in creams everywhere."

She also said doctors need to consider a patient’s needs. Although most would never prescribe only a week’s worth of insulin or heart medication, she often sees them dispense topical ointments for moderate to severe skin disease in small tubes.

"I always say tubs not tubes,” said Asiniwasis. "Give them enough so they're not driving back or undertreating themselves."

After Asiniwasis asked her young patients and their caregivers to describe barriers to healing their skin, they spoke of long wait times to see dermatologists, often travelling hundreds of kilometres at their own cost to seek care.

They also described the cost of skin care products in northern communities as ‘hyper-inflated’. Her patients and their families also face a sharp learning curve, as they adhere to strict bathing regimens, moisturizing, recognizing signs of infection, and learning to use topical ointments effectively.

Asiniwasis said resources in rural and northern communities for follow-up care are often limited.

“Many children will improve with time, but a lot of them also will go on to have problems as an adult,” Asiniwasis said. “There is some literature now suggesting there are observed associations of chronic skin inflammatory disease like [moderate to severe] psoriasis, for example, being associated with arthritis, cardiovascular disease, diabetes. With atopic dermatitis, there are concerns around bone health and eye health. Even some observational studies suggest there might be cardiovascular links."

“We can really tell someone a a lot about someone's health by looking at their skin.”