History of infectious diseases and vaccination: New USask course features an innovative interdisciplinary approach

As people around the world wait to receive one of several COVID-19 vaccines developed to help end the coronavirus pandemic, a timely new University of Saskatchewan (USask) course will explore interdisciplinary perspectives on infectious diseases and inoculation.

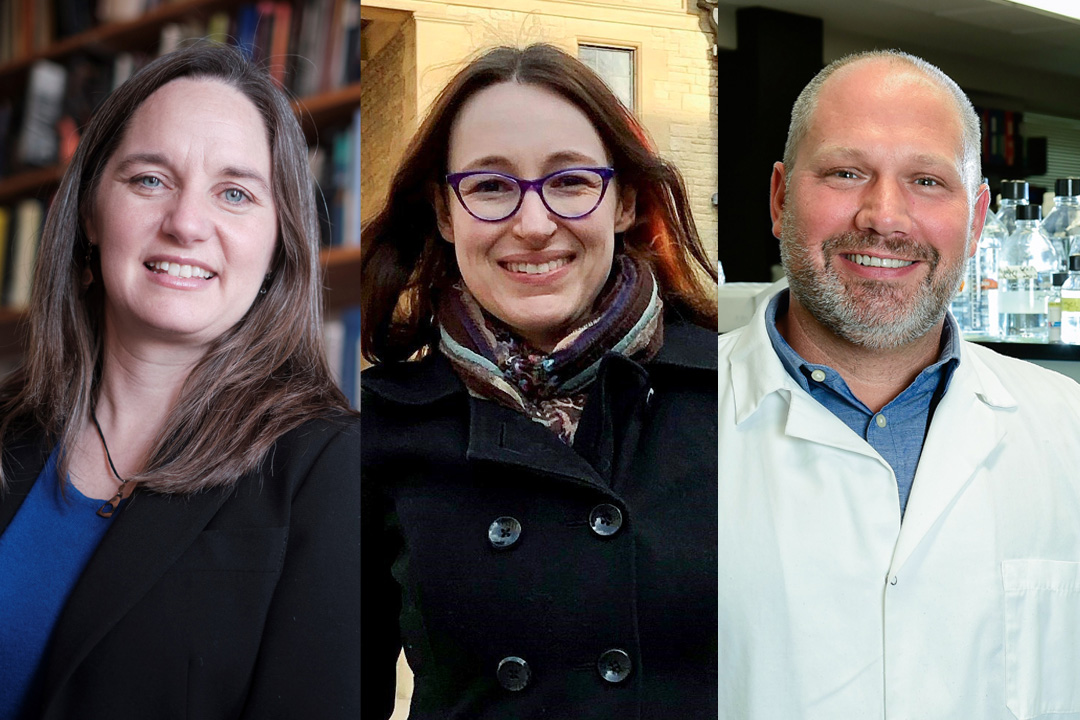

By SHANNON BOKLASCHUKThe course, HIST 237: History of Infectious Diseases and Vaccination, will kick off in January as USask’s second-term classes begin. The course will be taught by two medical historians from the College of Arts and Science, Dr. Simonne Horwitz (DPhil) and Dr. Erika Dyck (PhD), alongside Dr. Scott Napper (PhD), a professor of biochemistry, microbiology, and immunology in the College of Medicine who serves as a senior scientist at the Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization-International Vaccine Centre (VIDO-InterVac). Instruction will be delivered remotely, as most USask classes continue online due to the ongoing global health crisis.

Horwitz said the new co-teaching collaboration will demonstrate to students from various disciplines that complex issues such as COVID-19 can’t be solved by the sciences, social sciences, or humanities alone.

“When we think about dealing with infectious diseases and pandemics, we immediately think about the scientific solutions, vaccines, and medical cures—but one look at how the COVID-19 pandemic is playing out tells us that that is only one part of the story,” she said. “Context, history, and human behaviour matter. We will not be able to deal with this pandemic with science alone. We need to understand how epidemics can highlight social tensions, the ways in which race, class, gender, and where you live all affect mortality and morbidity—these are the lessons of history and the humanities.”

As a fellow historian of medicine, Dyck is also interested in looking back at previous health crises. Examining the past “helps us to gain perspective and pay attention to outcomes that might not be directly related to the disease per se,” she said.

“For example, we know that past pandemics caused a breakdown of social order, divisive campaigns about personal liberties, or anti-science attitudes that combated public health authorities—themselves often battling to get a grip on the science behind the spread of disease,” she said. “These kinds of protests are nothing new today, but studying them in history helps to remind us that pandemics are not ever just about diseases and vaccines, but so often they are about the stories we tell each other as we try to cope with uncertainties.”

In June 2020, Dyck and other USask researchers launched the COVID-19 Community Archive to capture people’s everyday experiences during the current pandemic as well as formal responses to the health crisis. The digital archive continues to welcome submissions from local residents—photographs, social media posts, videos, and personal reflections—that chronicle individual and collective experiences related to the pandemic. Students enrolled in the HIST 237 course will also be invited to contribute to the community-driven project, she said.

For Napper, a biomedical scientist, teaching a history course will be a new experience—and he said he’s “extremely grateful for the opportunity to be guided by two medical historians who are renowned for both their expertise and teaching.” He has always been fascinated with the stories underlying key moments in science—such as the personalities, motivations, and struggles of the people involved, the contexts in which the discoveries occurred, and the responses of their peers and the public—noting the timing for the launch of the new USask course is “tragically perfect.”

“As we struggle through this pandemic, there is a clear need for multidisciplinary approaches to manage the threats imposed by infectious diseases. Developing an effective vaccine is a critical, but incomplete, solution. Other disease control measures, such as masks and distancing, are also critical to minimize disease spread. The success of these efforts is heavily dependent upon the degree of public trust and support, which will either enable, or hamper, their utilization,” said Napper.

“These challenges aren’t unique to COVID,” he added. “For example, some the greatest challenges identified in containing the Ebola outbreak were community resistance; efforts to eradicate polio through vaccination have fallen short due to challenges facing communications strategies of immunization programs; and vaccine hesitancy is listed by the WHO (World Health Organization) as one of the greatest threats to global health. Clearly there is a need for a strong united effort by the biomedical and social sciences.”

Horwitz, Dyck, and Napper plan to teach the first part of the history course synchronously. In the second part, students will work together in groups—specifically designed to include people from various academic disciplines—as they explore and analyze disease scenarios from different historical periods and from different global locations. Horwitz said the central question of the assignments will be: why should we remember this disease and its management as we face new pandemics?

“Teaching this class with historians—one who focuses on the global south and one who focuses on the global north—and a scientist who specializes in vaccines and infectious disease is the perfect opportunity to give students this complex picture,” she said. “It also models, to both the humanities and science students, how these kinds of collaboration can work.”

Article re-posted on .

View original article.