Imaging inflammatory bowel disease with ultrasound microbubbles

A University of Saskatchewan (USask) researcher is developing ultrasound microbubbles to create a non-invasive, painless, and fast way to identify inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

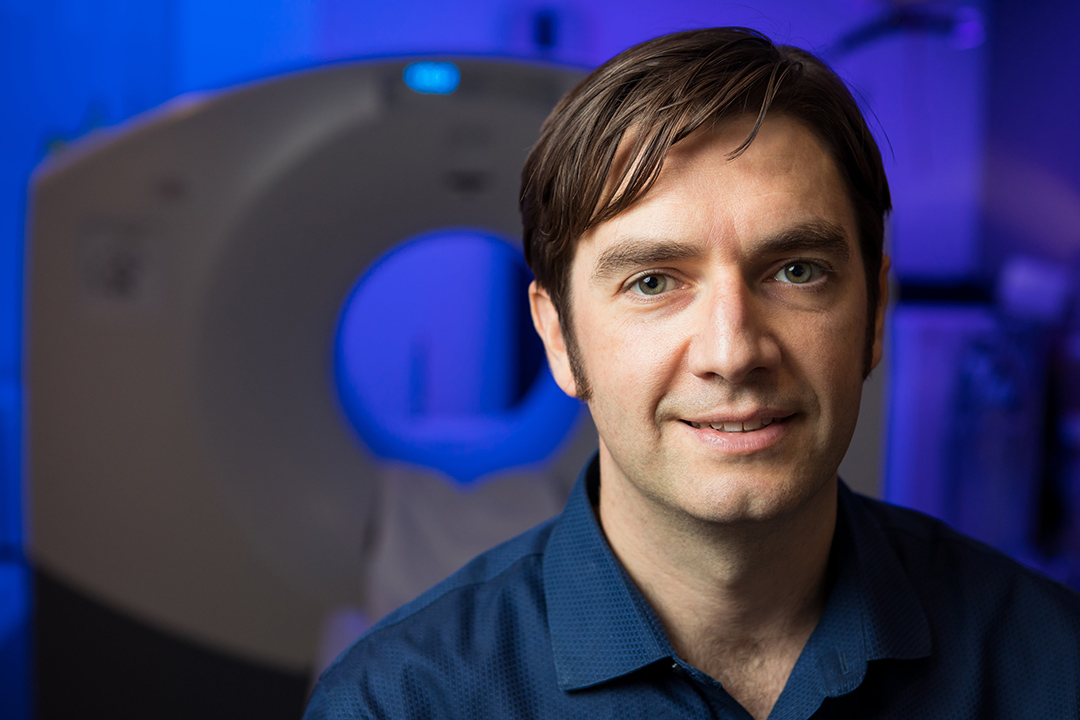

By Kristen McEwenDr. Steven Machtaler (PhD), an assistant professor in the Department of Medical Imaging in the College of Medicine, and his team recently received funding from the Canada Foundation for Innovation to explore this new imaging method for IBD.

“We’re trying to make targeted microbubbles that are inexpensive enough to be used in the clinic,” he said. “Our main goal is to develop a contrast agent that we can give to people. Especially for patients with inflammatory bowel disease, we need tools to accurately monitor the amount of inflammation going on.”

By using microbubbles—an ultrasound contrast agent that can be modified to stick to markers of inflammation—that are about one-twentieth the width of a human hair, Machtaler and his team are able to track how immune cells navigate the network of blood vessels in our vascular system.

“For our work, we really focus on where the immune cells are going,” Machtaler explained. “We study the immune system and how immune cells use the vasculature as a highway to get around the body.”

Machtaler’s team highjacks the immune cells’ approach used to navigate blood vessel networks in our bodies to find areas of disease, and uses it as an imaging targets, in this case for ultrasound scans.

If there is an area of inflammation on an individual’s arm, the inflamed cells cause the blood vessels in the area to start expressing proteins, which are designed to catch and recruit immune cells. These proteins essentially act like Velcro to catch immune cells, Machtaler explained.

“We add on antibodies to our contrast agent—our microbubbles—that stick to these Velcro proteins,” he said. “That allows us to image where immune cells are moving out of the vasculature into the tissues where there is inflammation. It gives us a really nice way to measure the inflammation in tissues like in the bowel.”

The most common way to identify and treat IBD in patients is through endoscopy, a procedure that involves physically inserting a camera into the upper or lower gastrointestinal tract. However, endoscopy also can’t always access small regions of the bowel.

In Canada, the prevalence of IBD has been rising, affecting about one in every 150 Canadians. The number of pediatric patients diagnosed with IBD is also increasing over the years, Machtaler said.

Other approaches to image IBD include MRIs and CT scans, which are expensive and have limited access.

Article re-posted on .

View original article.