Bio

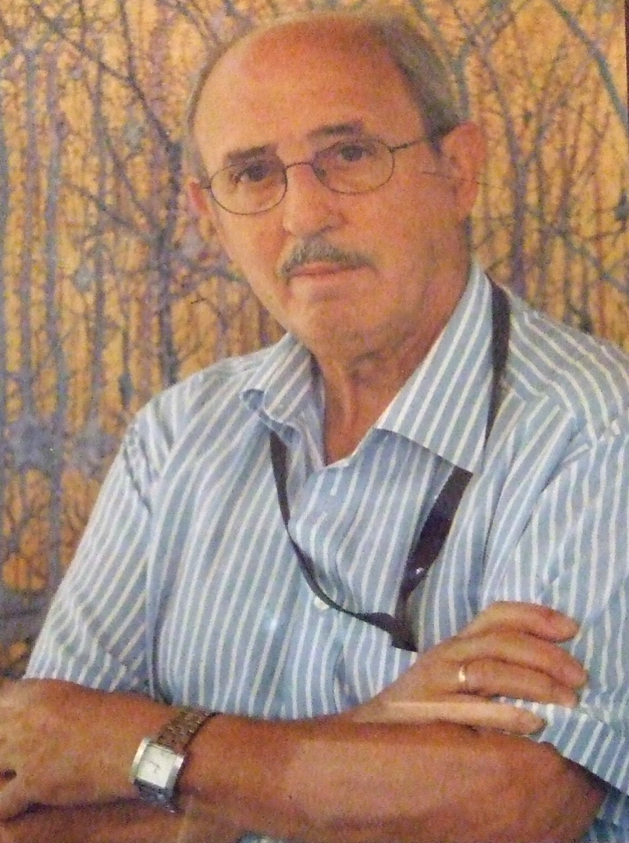

José Rodrigo García

José Rodrigo García, MD, PhD

José Rodrigo García, Madrid (born 1936), completed his Bachelor of Medicine at the Complutense University of Madrid in 1959. In 1964, he became the Assistant in the Neuropathology section of the Neurovegetative System at Cajal Institute.

His profound desire to serve society inspired him to organize several theoretical and practical courses dedicated to disseminating the techniques on the production of antibodies and the use of them with the help of immunocytochemical techniques.

In the early 1980s, his research largely took place in England as a Fellow of the Royal Society of London. The work initiated then in the Department of Histochemistry at Hammersmith Hostpital in London and continued in the Department of Pharmacology at the University of OXford specialized in the production and use of antibodies and immunocytochemical techniques resulted in publications with a global impact. "Calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) immunoreactive sensory and motor nerves of the rat, cat and monkey oesophagus" published in 1985 was the most cited worldwide in 1987.

Dr. García's Doctoral thesis entitled "Development of the facial acoustic complex of the white rat", received the highest distinction from summa cum laude in 1977. The same year he was appointed Head of the Section of Neuropathology of the Vegetative Nervous System, named Scientific Investigator in 1971, and in 1989 he was named Research Professor. During the next 50 years, the doors of his laboratory would remain open to all those in the University and in national or foreign research centres with desire to learn immunocytochemical techniques.

Throughout his scientific career, Dr. García held the position of President of the Association of Research Staff (API) (1976-1978), elected member of the Scientific Commission for the same area of Biomedicine (1989-1993) and the Governing Board of the CSIC (1989-1993). In addition, he was a member of the Governing Board of the Cajal Institute from 1976 until his retirement in 2006. Dr. García was a founding member of the Spanish Society of Histology and Tissue Engineering and of the Spanish Society of Neurosciences of which he was Vice President and Treasurer.

Following his retirement in 2006, Dr. García began his artistic career as a member and General Secretary of the Spanish Association of Medical Writers and Artists (ASEMEYA). ASEMAYA's cultural and artistic activity aims to spread scientific knowledge among citizens. Dr. García's artistic work can be found in the collection "Landscapes of the Brain", and has been widely exhibited in mueseums as well as in several biomedicine-related centres.

Interview

Q. You had been a scientist for so many years before starting to make art...what was your motivation to begin making sciart?

A. During my 42 years of work at the Cajal Institute of the Higher Council for Scientific Research (CSIC), there were many histological preparations that meticulously and personally were analyzed and studied. All of them made with different traditional techniques, such as those of Argentine impregnation, those of potassium dichromate with the help of the impregnation with osmium tetroxide and finally with the various immunocytochemical techniques. These techniques provided us with amazing images of different regions of both the Central and Peripheral Nervous System that were the foundation of some 250 publications made in international journals of recognized prestige in the area of neurosciences.

But really, and is what usually happens in the scientific world, these images are stored in libraries, with little diffusion among the public and I would also say, with little diffusion in the academic-university environment. In this way, how can we encourage interest in science among our adolescents and even among our university students? From this question comes the ignorance of biology, of the human body and of the existence of scientists who silently and surrounded by sacrifices try to create a better world without receiving anything in return. So at first the reason was to call the attention of the citizen to support men and women who work in science in order to increase the welfare of others.

Q. When you started to make sciart, did you approach the "projects" like a scientist?

A. I started doing Sciart in the first work that was published under the title "Study of vegetative innervation of the oesophagus. I. Perivascular endings in the year 1970 ". At this time it was necessary to use the drawing for lacking an adequate optical microscope and for the many planes that the image presented and that it was necessary to collect in only one. In this particular case, it was a punctuated drawing in Chinese ink that was taken through an eyepiece with a millimeter grid.

Q. What did you find different about the process of making your art and the process of doing science?

A. At that time I did not find any difference between doing art or doing science, especially in the specialty of neuro-histology, since in reality it was a matter of transferring a beautiful image of the nervous tissue contained in a histological preparation to a paper so that In the hands of a referee you could appreciate the scientific value that a beautiful image possessed. But immersed in this type of work, I thought that any topic of scientific interest could be conducted, that allows to know better the structure and function of the brain. Cajal pointed out that "The brain is like the garden that offers the researcher, captivating spectacles and incomparable artistic emotions", being the most suitable field where to satisfy the need to create art.

Q. Most often, we talk about how science can influence art. How did science influence your sciart?

A. I have the humble opinion that science is art, art being a complex mechanism with technical, scientific and even spiritual nuances that can serve to facilitate the diffusion and propagation of science.

Think of the great painters such as Michelangelo who used mathematics for his work in the Sistine Chapel and in which according to a team of scientists from the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine (USA), he painted specifically in the so-called "The separation of light and darkness", with great precision a brain and its union with the spine in the neck of the figure that represents God.

In the field of neuro-histology the entire beginning of the study of the nervous system is fundamentally based on drawings of both the systems and the neural elements that make up Dogiel 1865, 1893, Butzke 1872, Gerlach 1872, Meynert 18745, Golgi 1878, Luys 1878, Master of St. John 1879, Retzius 1890, Kolliker 1892, Room 1894, Held 1895, Dejerine 1895, Apathy 1897, Arnold 1898, Cajal 1899, 1901, 1903, 1904, 1905, Rossi 1909, Sobotta 1906, Nemiloff 1906, Alzehimer 1911, Tello 1917, Dek Rio Hortega 1920, De Castro 1920, Lorente de No 1922

Q. Do you think that art can influence science, and if so, how?

A. Nowadays, with the magnificent means of preparation and staining of tissues and microscopic observation, we can affirm that the structural images observed in nervous tissue are spectacular. In this sense, D. Pio del Rio Hortega pointed out: "The truths of science and the beauty of art are so amalgamated and confused in history that it can not be known if the histologist is passionate about science or about clothing; for the beauty of truth or for the truth of beauty. "

I believe that art finds its full potential to serve science, since it is so solid in its concept and results that it can not be modified by art, although this can serve science as we have indicated previously, acting as a mechanism for dissemination and dissemination, to the scientific world or to citizens

Q. Have you tried to use your "Sciart"? to influence science ?.

A. Not for the reasons explained in the previous section

Q. Aside from using art to communicate science, how can sciart help scientists better understand their work?

A. I believe that any scientist, when observing works similar to those represented by the paintings that make up the "Landscapes of the brain" collection, can establish a silent dialogue similar to that produced when a morphology is defined on a paper and around it we ask ourselves a series of questions seeking solutions to doubts at the moment unanswerable. On many occasions this silent dialogue, which is not used in daily life, is necessary to find solutions. This usually happens in the observer who contemplates a painting in a museum, a picture that not only facilitates spiritual tranquility but also the location of or solutions to their problems.

Q. How is your culture and worldview reflected in your sciart?

A. As a young man I went to an adorable village on the islands of Majorca to paint class that I left shortly after, although I had the opportunity to know the fundamental principles of painting and drawing as art. Always throughout my professional life some drawing or picture I made, always feeling true interest in the painting of the greats of Spain, Goya, Murillo, the fantastic Sorolla, Velázquez, Dali and Picaso. Its shapes, shadows and lights have been applied on occasions in the paintings that make up the collection.

This is recreated in those paintings that represent structures of the peripheral nervous system that accumulate on the canvas several planes taken from the gross histological preparations, an example of which is the perivascular terminations of the wall of the esophagus.

Q. Has working on your sciart changed your perspective of artists or of the artistic process?

A. The perception that I have of the artistic hand and the capacity of young talents in the elaboration of paintings of all kinds and lately in the creation of scientific paintings and drawings has not changed. Today there are true human values as artists, but drawing or scientific art needs very solid artistic and scientific knowledge to respond to the needs that are presented to them. It is therefore easier to find scientists doing art than artists doing science. In this sense, care should be taken that scientists during their academic training received knowledge about art and more specifically about the different artistic techniques that at a certain moment opened the doors for an adequate scientific and social communication.

Q. Has your experience doing "Sciart" changed your perspective in your own scientific work?

A. No, both aspects complement each other but one does not change the other simply facilitates the work and dissemination of scientific knowledge that triggers certain stimuli in the observer and can opt for training in the scientific development of any country.

Q. Has your artistic style or motivation to make art changed, and is that reflected in differences in your work at different times during the past years?

A. All my scientific-artistic activity has been carried out after my retirement in 2006 and has had as a goal, to achieve a good cultural level of the citizens with what would be able to raise a vigorous team of scientists trained to undertake novel research, which will contribute with dynamism to the hegemonic creation and the welfare of a people.

Participate

Gauthier(artist), and Erin Prosser-Loose (Research Equity & Diversity Specialist, College of Medicine).