Investment in 'hungry young wolves' yielding dividends

In 2016, the health of health research at the USask College of Medicine was failing. The school occupied the bottom rung in the Maclean’s university rankings for medical and science grants for medical/doctoral programs in Canada. And it accounted for just nine per cent of the university’s total research productivity, when the national average was closer to 40 or 50 per cent.

By Greg Basky for USask College of Medicine

This article is aligned with the USask College of Medicine's strategic directions.

_____________________________________________________________________

“At the time I was recruited to be vice-dean (research) back in 2016, it was clear that the college — in terms of research — was trailing in the rankings among the U15, the medical research-intensive universities,” recalls Dr. Marek Radomski. “When you look at the national or international stage, the might of universities is very much dependent on the might of the colleges of medicine. We didn’t really have a big impact on the research.”

While Radomski figured he knew what to prescribe for the ailing patient, he asked the college to commission an external review of the state of research in the college. An all-star team of researchers came to the same diagnosis that Radomski had after just six months in his post, that the college needed to introduce a pair of stimulus packages to revive its research: one to support and encourage existing faculty, and a second to recruit young up-and-coming researchers.

“The future of the college, and of the university, depends on new blood, on the hungry young wolves,” said Radomski.

In 2018, the College of Medicine introduced a recruiting system to court the best of the rising biomedical research stars; it began offering a generous startup package of funding, to equip them to quickly become competitive in national grant competitions.

To help the new faculty grow and succeed, the college also made available no-strings-attached research and career mentorship — to help early career scientists decide which grants to go after, when to apply for promotion, and whether their research is as strong as it could be. Seven “hungry young wolves” have joined the biomedical faculty, each receiving between $300,000 and $450,000 in seed money, along with other envelopes of funding.

The seven, according to Radomski, have responded “beautifully.” One of the first stars the college landed, Dr. Scott Widenmaier, arrived in July 2018. Since then, Widenmaier has secured more than twice as much external funding as the college provided him, including grants from the Saskatchewan Health Research Foundation (SHRF), the National Science and Engineering Council (NSERC), and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). The Heart and Stroke Foundation recently named him the country’s top new investigator, for his work on a cluster of diseases — diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and fatty liver — associated with obesity and aging.

The other six researchers, said Radomski, are also quickly distinguishing themselves. Dr. Kerry Lavender, who joined the medical school in September 2018, has developed a model in mice that could pave the way for the treatment of human respiratory diseases such as COVID-19 and other emerging viruses with the potential to become pandemic. Since coming to the college, Lavender has secured a $300,000 CIHR operating grant.

“These are just examples of how investing in people’s research careers pays off in dollars (for the College of Medicine),” said Radomski. “But more importantly, it changes the culture. The culture for achievement. The culture for productivity. The culture that everyone can be a top scientist.”

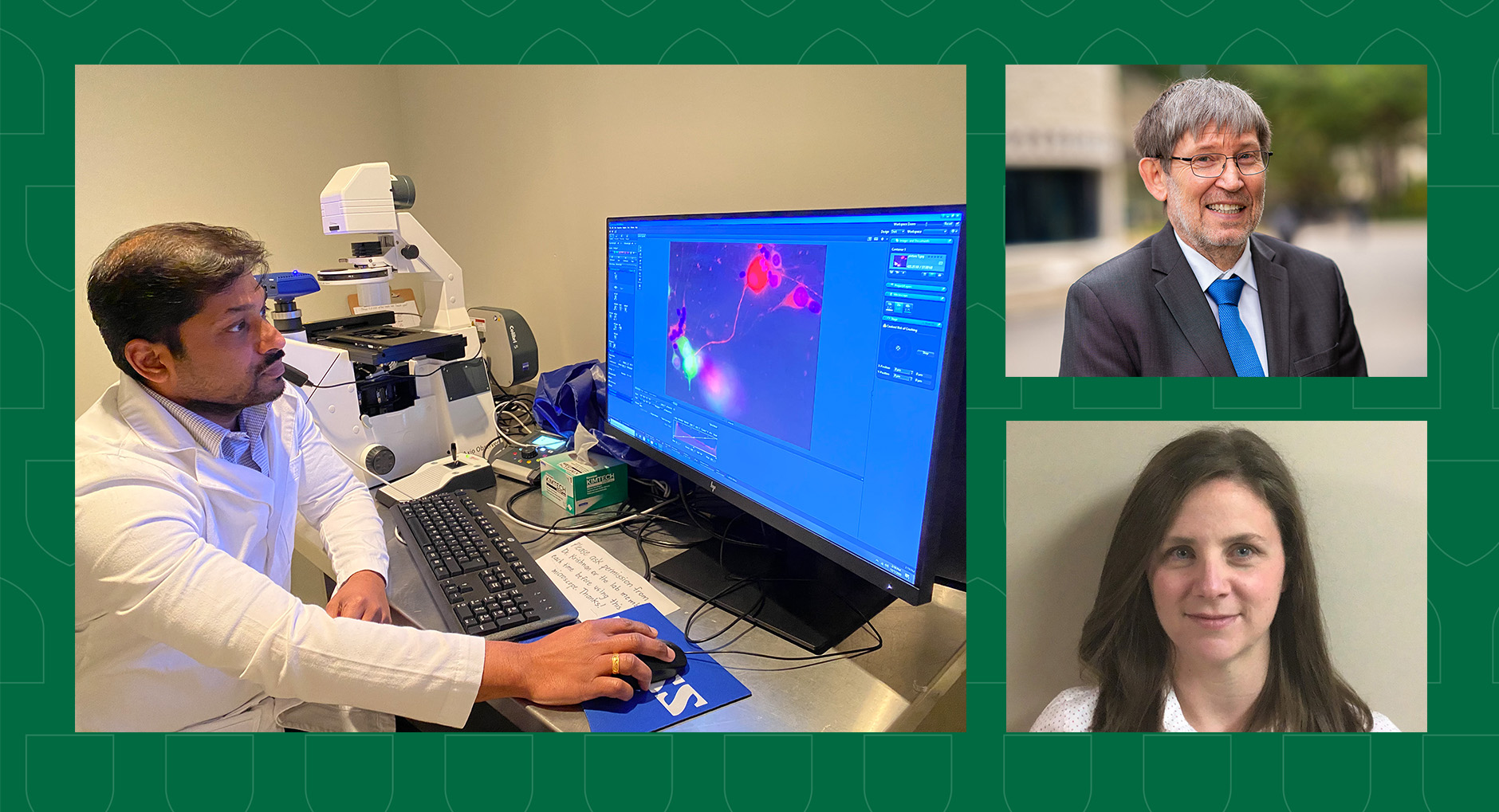

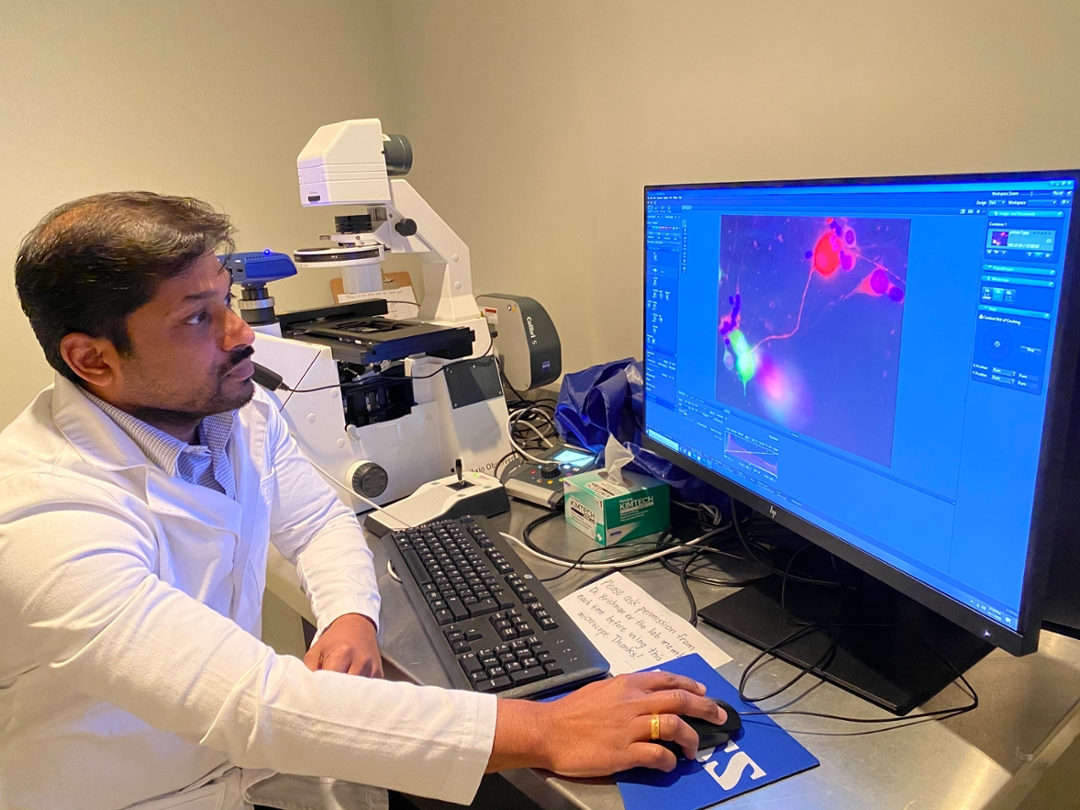

Meet two hungry young wolves

Anand Krishnan is exploring the contribution of the body’s nervous system in promoting cancer tumor growth. Recruited from the University of Alberta in September 2019, Krishnan said the College of Medicine’s generous startup funding was a major factor in his decision to come to USask.

“When we (early career researchers) look for faculty jobs, there are two things that matter most,” said Krishnan. “One is whether we get enough support to start a research program. So, is there enough money to procure the necessary equipment and bring in staff and trainees to our lab, until we can get some major funding? The support we get from the College of Medicine is tremendous.”

Krishnan has already brought in an NSERC discovery grant and is waiting to hear whether he was successful in a recent CIHR competition.

The other consideration, according to Krishnan, is an institution’s research environment. The college here, he said, has strong “clusters” in both neuroscience research and in cancer research.

“My research marries cancer biology and neurobiology, so it is good to have senior researchers in these areas, to collaborate with and gain additional perspectives on the questions I’m asking.”

Researcher Jenny-Lee Thomassin was wrapping up a post-doctoral fellowship at the Institut Pasteur in Paris in spring 2019, when she saw the USask faculty posting. She was familiar with the college’s Department of Biochemistry, Microbiology and Immunology, because now-retired professor (emeritus) Peter Howard had been exploring some of the same questions she was asking about how bacteria use nanomachines to manipulate their environment and cause infection.

Besides the healthy startup funds, Thomassin was also attracted to the department’s reputation for being supportive and collegial.

“It was well known that this is a department where people work well together and support one another’s research programs,” said Thomassin, who has already secured an NSERC discovery grant since coming to USask in May 2020. “If you look back through the years at the U of S, there have been a lot of people who have worked together and supported one another here.”

Thomassin appreciates that the college is going through a period of renewal with a mix of senior, mid-career, and junior researchers. She likes that she can tap into the experience of more seasoned scientists.

And, as a young up-and-comer, Thomassin said, “It’s nice to have colleagues at the same career level as you, who you can discuss your work with, who can support one another, move through the ranks together, and celebrate each other’s successes.”

Strong research program benefits Saskatchewan patients

A medical school’s research productivity has a multiplier effect, according to Radomski. “That’s money. That’s prestige. That’s the ability to recruit the best doctors to the province,” said Radomski.

“The best doctors will be attracted to a strong academic environment because they can grow, they can publish, and they can show how excellent they are. So there’s a direct translation between the quality of the physicians, scientists, and academics, and the type and quality of service you get as a patient. Our mission (in academia) is to do everything we can to contribute to society, to the health of people in Saskatchewan.”

Krishnan’s goal is to develop new cancer treatments that shut down the mechanism that causes nerves to secrete the nutrients that stimulate abnormal proliferation of cells in tumors.

“What I am trying to understand is what are those growth factors that are turned on, that are coming from the nerves that support the tumor, so that we can cut off the supply of those growth factors and limit the progression of the tumor in that way,” said Krishnan.

He’s also exploring how to use those same growth factors to speed up nerve regeneration, to prevent muscle atrophy in patients who have sustained nerve damage.

With Thomassin’s research, the end game is figuring out how to block the nanomachines in nasty bacteria like E. coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae from sending out their infection-causing cargo. The latter pathogen is everywhere — on the ground, in water, in animals, in our guts, on our skin — and it’s quickly becoming resistant to all existing antibiotics.

“We don’t fully understand how this classic Klebsiella goes from just being there to making us really sick,” said Thomassin. “We have to understand how it’s interacting with its environment to be able to understand how we can get rid of it.”

By the numbers

The stimulus-fueled momentum built up prior to COVID helped the college’s researchers maintain the same level of funding and grant success in 2020 as it did the year prior. Radomski said the fact that USask continued to recruit during the pandemic signaled to the outside world that its College of Medicine is a dependable institution that will carry on its research mandate regardless of challenging circumstances.

The medical school’s investment in rising research stars — along with its internal funding offerings for existing faculty — is paying off. By 2018, it had climbed one rung, to 14th spot in the Maclean’s rankings. In 2019, the USask medical school jumped to 12th position, one position ahead of Dalhousie and nipping at the heels of the University of Calgary. Figures compiled by Research Infosource rated USask the country’s #1 medical school for its remarkable 39 per cent increase in research income during fiscal year 2018-19.

Say what you will about the importance of rankings, there’s no escaping the fact that they matter to students deciding where to apply, and to the faculty working at universities.

“The catch phrase of our university is ‘the university that the world needs,’” said Radomski. “In order to be needed, we need to be competitive. Otherwise, nobody’s going to take care of our existence.”

Currently up for renewal after his first five-year term, Radomski is confident the health of the college’s research program is growing stronger.

“It's quite incredible how this institution of hungry young wolves can work to spur and transform the culture, bring in the funding, and basically provide a more brilliant future.”