Creating programs that make a difference motivates Thunderchild

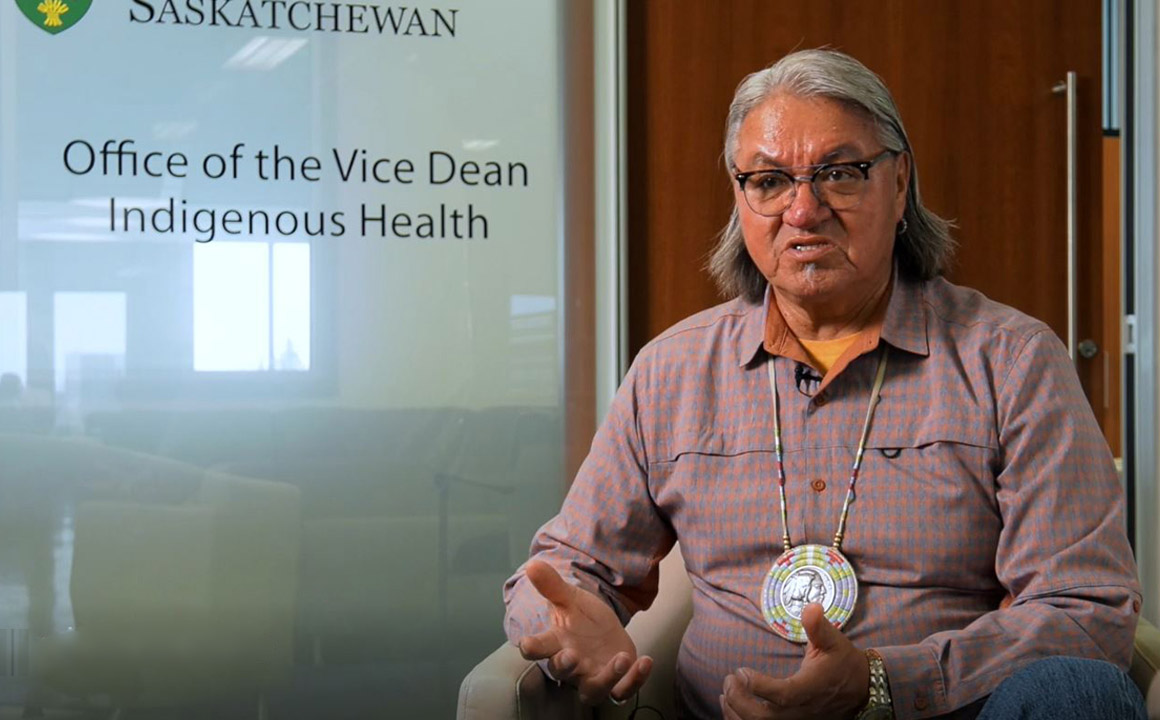

Harvey Thunderchild’s life path has been a fascinating journey. It has taken him across Canada and into the United States, and most recently has led him to his new position as the cultural coordinator in the Office of the Vice-Dean Indigenous Health and Wellness at the USask College of Medicine.

By USASK MEDIA PRODUCTION with KATE BLAUIt’s a path he describes as a “complete circle” that involved his own desire to be better no matter the odds he faced personally. His connection to his roots as an Indigenous person played a significant role in his life and his success. He is a member of the Thunderchild Cree Nation, located 90 km north of North Battleford, Saskatchewan, and was raised in his community by Elders.

“My Indian name is Wapistum, meaning White Horse, and was given to me by the Elders that raised me at birth and Ahchapi, meaning bow and arrow, that was given to me by another set of Elders growing up in my community,” Thunderchild said.

He describes himself as a traditional man who believes in his own Cree culture, and is involved with all cultural ceremonies. He grew up learning ceremony from his late grandfather, Ed Thunderchild, and father, Victor Thunderchild, and other extended family members involved in the cultural practices and beliefs of their community.

Thunderchild started his new position on October 3 in a new unit that’s been formed in the College of Medicine to explore how to work with healthcare providers and deliver education to better align with the needs and world view of Indigenous people.

“My responsibility here is to advocate protocols,” he said. “I do a lot of cultural diversity, Indigenous engagement, the protocols we have to follow when we do things, and usually I get asked to speak to grads about cultural protocols, about understanding Indigenous way of life, how we do things, who we are as Indigenous people.”

He’s already seen results of the knowledge he is sharing, getting thanks from non-Indigenous people who have told him they are learning things they didn’t know before. It’s not new for Thunderchild, who used to explain his own traditions to teammates before they went out onto the ball diamond. He played professional fastball for 22 years from Vancouver to Toronto and points in-between.

Another aspect of his role involves connecting with Indigenous healthcare providers in the communities and making connections with health directors at various Indigenous organizations in the province. He’s well set up already for this having worked for his home community, Thunderchild First Nation, as its health director for four years starting in 2002.

From this and his own life experience, he has been directly involved in helping address challenges and concerns Indigenous people experience in accessing and interacting with the healthcare system. He has helped address fears and improve understanding of unfamiliar language, procedures and processes for Indigenous people, and shared information and knowledge with non-Indigenous people so they can provide more culturally sensitive care to Indigenous people.

“As an Indigenous man I know there's a lot of things that Indigenous people don't understand about medicine and they're fearful, so this is where I come in and I can articulate information.”

Thunderchild’s focus on health started in a very different way as a younger man.

“I'll be 68 this coming Friday and I've been active all my life, so that I don't like being overweight.”

He used to find opportunities to play baseball with teams that needed to pick up a player. It led to a professional fastball/baseball career spanning 22 years as a catcher. He also played professional golf in Michigan for 12 years. He played hockey in both Canada and the United States. He’s a traditional dancer and singer at pow wows, keeping his cultural connections strong and staying active and fit.

His work for various organizations in different parts of North America included developing curriculum for a two-year program for home care nurses providing care to chronic patients in First Nations community; he’s been a liaison worker for correctional institutions, working with inmates and their lawyers in areas that involved a range of needs, including mental health, case management and pre-release programs. Often, when the lawyer for one of his clients was tied up elsewhere, he went before judges with the inmate to represent them.

He developed an employee assistance program for a casino organization employing more than 5,000 people while living in Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario. He worked there for 12 years and was key to addressing a staff turnover problem he’d been hired to help change. A key component of the program’s success was addressing mental health issues. While the turnover issue was greatly improved, more importantly employees who needed support had access ultimately to a total of 10 social workers. The program grew and extended to assisting patrons with gambling issues, as well, and was a model for other casinos and organizations.

“Where I'm at today, I can look back at how I was instrumental in a lot of different things in the health area, where I can use it here. It's one of the things that helped me a lot, you know, especially mental health.”

When he was 30, he graduated with a sociology degree from the University of Saskatchewan and then achieved a bachelor’s degree in human resource management in Sault Ste. Marie when he was 47. While building his career, pursuing university degrees and playing professional sports, he raised his four children and six that he adopted as his own as their stepfather. His involvement in sports played a big role in his time and relationship with his kids.

“My biggest fans were my kids. If they were happy watching me, you know that was a great accomplishment.”

He sees the reward for time spent with his children now in the time they spend with their own kids, and their own career successes in teaching, filmmaking, finance and law.

“It's all about kids, you know, when you raise your own kids, and you watch them flourish and the successes that they have. That makes you happy.”

It might seem like a perfect time to sit back and enjoy the fruits of an active and successful life, but Thunderchild loves creating things that make a difference and is excited by his newest professional challenge.

“We're still in that process of trying to identify what our mission should be, what our goals are,” he said. “I grew up in a traditional way of life. I always observed my Elders, my grandparents, my father, anybody in my family or extended family—the way they do things. And I think what attracts me in the position here is, you know, as an institution sometimes we take shortcuts, and sometimes it's detrimental. I can tell or show people why we do the things we do.”