Biomarker research could help improve early concussion diagnosis

The NHL saw a disturbing increase in concussions between 2009 and 2012

By Marg SheridanWith winter in full swing, and the IIHF World Junior Championships just around the corner there’s only one sport on the minds of Canadians from coast-to-coast: hockey.

But while fans continue to debate whether Sidney Crosby can repeat his Hart Trophy-winning season, or which Canadian teams will once again miss the playoffs, they’re also talking about concussions.

In fact, a study published in 2013 by researchers at St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto, showed that while the league is cracking down on hits to the head, the NHL saw a disturbing increase in concussions between 2009 and 2012. Their research identified 44 concussions during the 2009-10 season, a number that had nearly doubled to 82 in 2011-12.

And despite that research being centered on the NHL, concussions have been a big topic of conversation on the U of S campus for a while now with research being done by Dr. Chanzig Taghibiglou and Dr. Nam Pham taking centre-ice, so to speak.

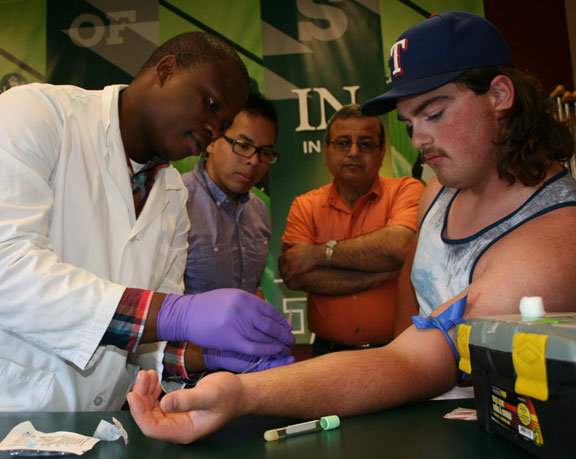

The pair have been working on a way of isolating a potential biomarker that can help to diagnose concussions using only a drop or two of blood – and it’s research they’ve been doing with the help of some of the U of S Huskies.

And while the Huskies are proactive in regards to educating players, coaches, trainers and even parents of the possible signs of a concussion, having the ability to quickly, effectively, and definitively diagnose one would help keep the athletes safer.

“We want to encourage that kids do participate in sport,” explains Rhonda Shishkin, Huskies Athletics’ Head Therapist. “And if they are aware of concussions, and signs and symptoms of concussions, we can manage them quite well - The first thing that we do here is we provide our athletes, coaches, trainers with an education about concussions.”

It’s a concussion management system the university has had in place for some time, but it’s not perfect.

“Right now the diagnosis of concussion is clinical,” said Shishkin. “(There’s no) specific test we can do to see if someone has a concussion - we use a battery of tests and come up with a clinical diagnosis. So a biomarker would be a handy tool.”

Which lead to the Huskies becoming involved with Taghibiglou’s research.

“We collected volunteer plasma samples and established the normal level of plasma protein numbers,” said Taghibiglou. “Then we collected samples post-concussion with the football and hockey players and discovered the same protein biomarker also increased post-concussion, and we concluded that it could be used for detecting concussion in athletes.”

These protein biomarkers can have a widespread impact on the detection of concussion, especially considering that concussions can present differently from patient-to-patient – from anything like dizziness and headaches to nausea and fatigue.

While the bulk of media attention about concussions focuses on professional athletes, Taghibiglou’s research has also recently extended to working with the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto to help determine whether the kit could work with youth and children. Since the biomarker study is relatively new, they hadn’t yet determined the normal value for children, which would allow them to calculate what would be considered heightened protein value numbers.

“A lot of the victims of sport concussion are children and youth,” said Taghibiglou. “So we joined SickKids, and we got some blood samples from them to define normal values for children and youth. And now we’ve measured and defined that value and are in the process of submitting it to a journal.”

The end game with regard to the biomarker research is to create a kit, not unlike the kits used to monitor diabetes, which would allow clinicians to determine whether the athlete, child, or accident victim is in danger of developing a concussion or brain trauma.

“If we detect concussion early and give some rest to the athletes, 99.9 per cent of cases the athlete will recover – depending on the extent of the injury,” explains Taghibiglou. “But if we miss the concussion and the athlete starts playing again, or getting repeated concussions, in some cases the outcome is disastrous - and in severe cases can cause death.

“So early detection is crucial for clinicians - and for families.”