Billroth: A surgeon and an artist

Bringing new methods of investigation and practice

By Dr. Francis Christian, FRCSEd, FRCSC

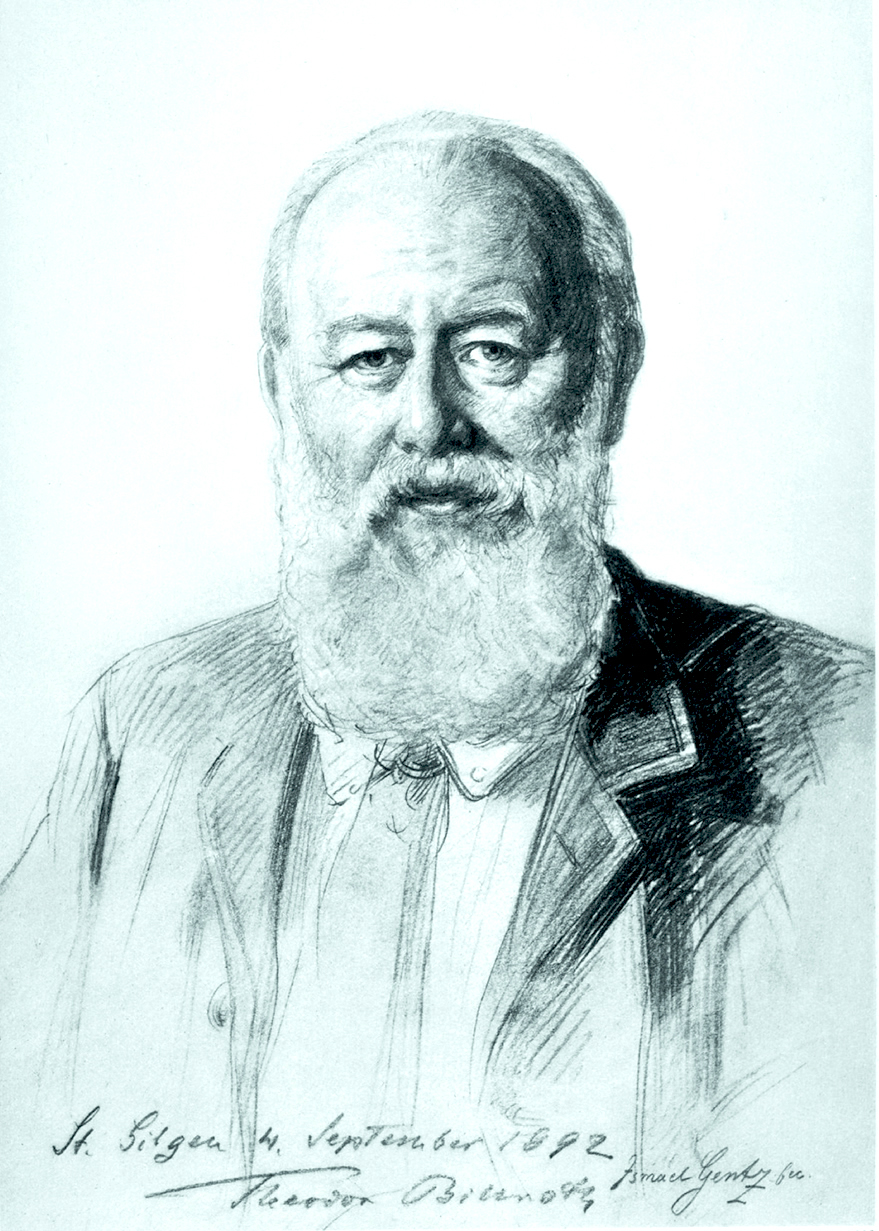

In the Vienna of the latter half of the 19th century, the German immigrants to the once-mighty seat of the Austro-Hungarian empire, recognized Vienna’s eminence in the sciences, but also in the arts. It was this combination of the creative pursuits of mankind that acted like a magnet, drawing in perhaps the leading surgeon of the nineteenth century Christian Theodor Billroth (1829-1894) to take over the chair of surgery in Vienna in 1867.

Billroth quickly brought in new methods of investigation and practice to the Viennese school, some of which he had learned as a pupil of the famed German school of surgery under Bernard Von Langenbeck. Moving away from a simplistic understanding of disease based on cadaveric dissection, Billroth advocated to his devoted surgical disciples, an understanding of surgical disease based on anatomy and surgical physiology and pathophysiology. It is well known of course, that he introduced bold, new operations on the larynx, the esophagus and the stomach (we still speak of “Billroth 1 and Billroth 2 gastrectomies), but he also insisted that his students practice first on doing the same operations safely, on animals. Very uniquely for his time, he introduced an audit of his own results - and famously stopped doing thyroidectomies when he realized the mortality rate in his cases was unacceptable (he started doing them again, several years later, after another of Langebeck’s pupils Theodor Kocher had made thyroidectomies safer than ever before). We in North America have a direct link to Billroth as well, since William Halstead brought back to Baltimore the residency system of surgical training which he had learned from Billroth and from the German surgical school.

At the age of 19, the talented pianist Theodor Billroth had been persuaded by his parents to pursue medicine as a career instead. As it turned out, Billroth devoted an equal energy to both his life-long pursuits and credited music with providing him the inspiration and wherewithal for his remarkable scientific achievements. Throughout his furiously busy career as a surgeon, he made considerable time for his musical pursuits.

By the time he was in Zurich (1860 - 1867) he had taught himself the violin and viola and had become proficient in both. He was sufficiently well recognized as a musician to be offered to guest conduct the symphony orchestra in Zurich. This was also where he was introduced to the great Austro-German composer Johannes Brahms (1833-1897).

For those who are not yet familiar with the beautiful work of Brahms, take a look at this YouTube video.

When Billroth moved to Vienna at the age of 38, he immediately sought out Brahms. Within a few months, Billroth had converted a large room in his home into an ornately decorated musical studio. Several decades earlier, the same house was visited by Beethoven and Billroth wrote in a letter to Brahms, "It is interesting to me that Johann Peter Frank and Beethoven met in my house and that a similar relation - let us not be arrogant! - exists between you and me one hundred years later. Beethoven wandered in this direction: must not Haydn, too, have had rehearsals . . . in this house? . . . What a noble triad: Haydn, Beethoven, Brahms!"

For the next three decades, Billroth’s home was the regular meeting place of Brahms himself, together with Billroth and a few other musicians, who played together in a musical quartet. Brahms would send his compositions first to Billroth for his comments, before considering it for performance - so great was his regard for his musician-surgeon friend. In deep appreciation, Brahms dedicated two of his three String Quartets (the A minor and C minor quartets) to Billroth. They would also allow aspiring, talented artists to perform Brahm’s compositions in the home studio - and it was said that if the performance was outstanding, champagne would be passed round (if less than overwhelming, beer was the standard drink!).

Toward the latter few years of his life, Billroth started work on a new investigation into the “Physiology of Music” and the book was published posthumously by his musician friends, after his death.

I have already summarized the central importance of an education and engagement in the humanities for the surgeon, elsewhere: online - University of Saskatchewan department of Surgery - Surgical Humanities: http://www.medicine.usask.ca/surgery/surgical-humanities/index.php

Billroth of course, is only one of several examples of scientists and surgeons who have found inspiration for their scientific work, in the arts and humanities. In a letter to his art historian friend Lubke, Billroth wrote, “It is one the superficialities of our time to see in science and in art, two opposites. Imagination is the mother of both.”

And in more recent times, Albert Einstein himself wrote, that for creative work in science, “imagination is more important than knowledge. Knowledge is limited; imagination encircles the globe.” “After a certain high level of technical skill is achieved, science and art tend to coalesce in esthetics, plasticity, and form. The greatest scientists are artists as well.”

References and Further Reading

- My information about the facts surrounding Billroth’s life as a surgeon and musician is drawn chiefly from two sources: F. William Sunderman : “Billroth as Musician” ; Bulletin of the Medical Library Association, Vol 25: No. 4; 1937 and from : Tatjana Buklijas : “Surgery and National Identity in late 19th century Vienna” Stud Hist Philos Biol Biomed Sci. 38(4): 756–774, 2007

- The quotations from the letter of Keats and from the works of Albert Einstein are from “The letters of John Keats” collected by Robert Gittings. Oxford University Press, 1970. And “The Expandable, Quotable Einstein” collected by Alice Calaprice, Princeton University Press, 2000

JOURNAL OF THE SURGICAL HUMANITIES

One of the initiatives of the Surgical Humanities program is the launch of our new journal - Journal of The Surgical Humanities. The journal has both an online and a print presence and will be published twice a year. Submissions to the journal are accepted in two categories:

- Written Work : poetry, essays and historical vignettes.

- Visual Work : submissions in digital reproductions, of paintings, photographs and sculpture.

The journal is open to submissions and for details of the submission guidelines, please visit the Surgical Humanities.