Is there a bilateral bias in perception of passion?

80 per cent of people intuitively turn to the right when kissing a partner, why?

By Marg Sheridan

Mae West once said ‘a man’s kiss is his signature,’ and while every kiss may be different, Jennifer Sedgewick is researching one common, observable trend: lateral biases.

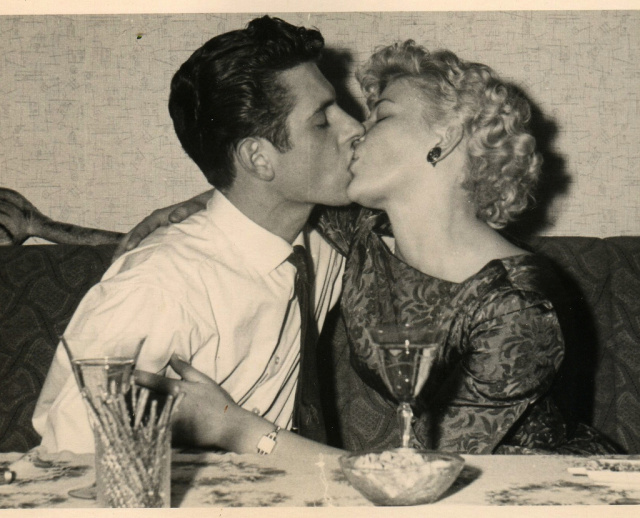

“People consistently turn to the right when kissing more often than the left – usually around 80 per cent of the time,” explained Sedgewick. “Usually that’s an intuitive decision. (So) we wanted to investigate if this behavioural bias was associated with perceptions of a kiss – that is, does the kiss appear to be more passionate when it is oriented as a right-turn kiss?"

And that’s the question that Sedgewick asked in a survey posted in PAWS a month ago. The team compiled stock photos of couples kissing and posted the same picture, with one having being flipped vertically as a mirror image, asking participants to choose the one that appeared to be more passionate.

“Interestingly, further study found that when participants kissed a neutral stimulus, a human-sized doll, they presented a comparable right-turn bias,” she stressed. “Even when the doll was positioned to receive a left-turn kiss; participants would overcompensate their head-turn to still give a right-turn kiss.”

So if not handedness, which multiple studies have shown didn't impact the decision, what could be influencing this bias?

Sedgewick explains that the current theory for this “kissing bias” is that it is a product of a right head-turning bias observed during early infancy. “From as early as 38 weeks of gestation to around six months of age, infants make pronouncedly more right-head turns, and it is thought that this turning bias re-emerges as a kissing preference in adulthood.”

This isn’t the first time that Sedgewick has looked into bilateral kissing preferences – a content analysis study she did last year that looked at kissing biases in pictures, which included parents kissing their children, was picked up by international media including Cosmopolitan magazine. The results from that analysis were the catalyst for this ongoing study because they found that the bilateral kissing preference changed depending on the context.

“When we looked at parents who were kissing, (they) had a huge right turn bias, so again around 80 per cent,” Sedgewick explained. “But when we look at parents kissing their kids, we found a left-turn bias.

“So we were trying to ask whether a right-turn kiss looks more passionate than a left-turn kiss - maybe it’s something to do with emotion?”

Sedgewick, who is a masters student in the cognition and neuroscience stream of psychology, will be transferring to a marketing PhD shortly, and her research on bilateral biases is one she expects to be transferable between the two disciplines. Lateral biases are something that translates to more than just kissing, and Sedgewick explained that a similar marketing study was done in their lab in 2011 that found that photos of merchandise lit from the left ultimately had a higher purchase intention among consumers than items lit from the right.

“So, say when looking at a movie poster, or an advertisement where there’s a couple kissing, that research could potentially lead something like a higher purchase intention or a heightened liking of the picture if it’s something that looks more intuitive for the person,” Sedgewick said of her career change. “So I might do something more applied like that, similar to the lighting bias study, where it might give some type of practicality to the kissing research.

“It’s informing how differences between our brain hemispheres can facilitate behavior, or how learned behaviours can influence lateral biases.”